Note: I wrote the original version of this essay in January of this year for the graduate course English 504: Posthumanism with Dr. Jason Bryant at ASU on the topic of Donna Haraway’s book When Species Meet.

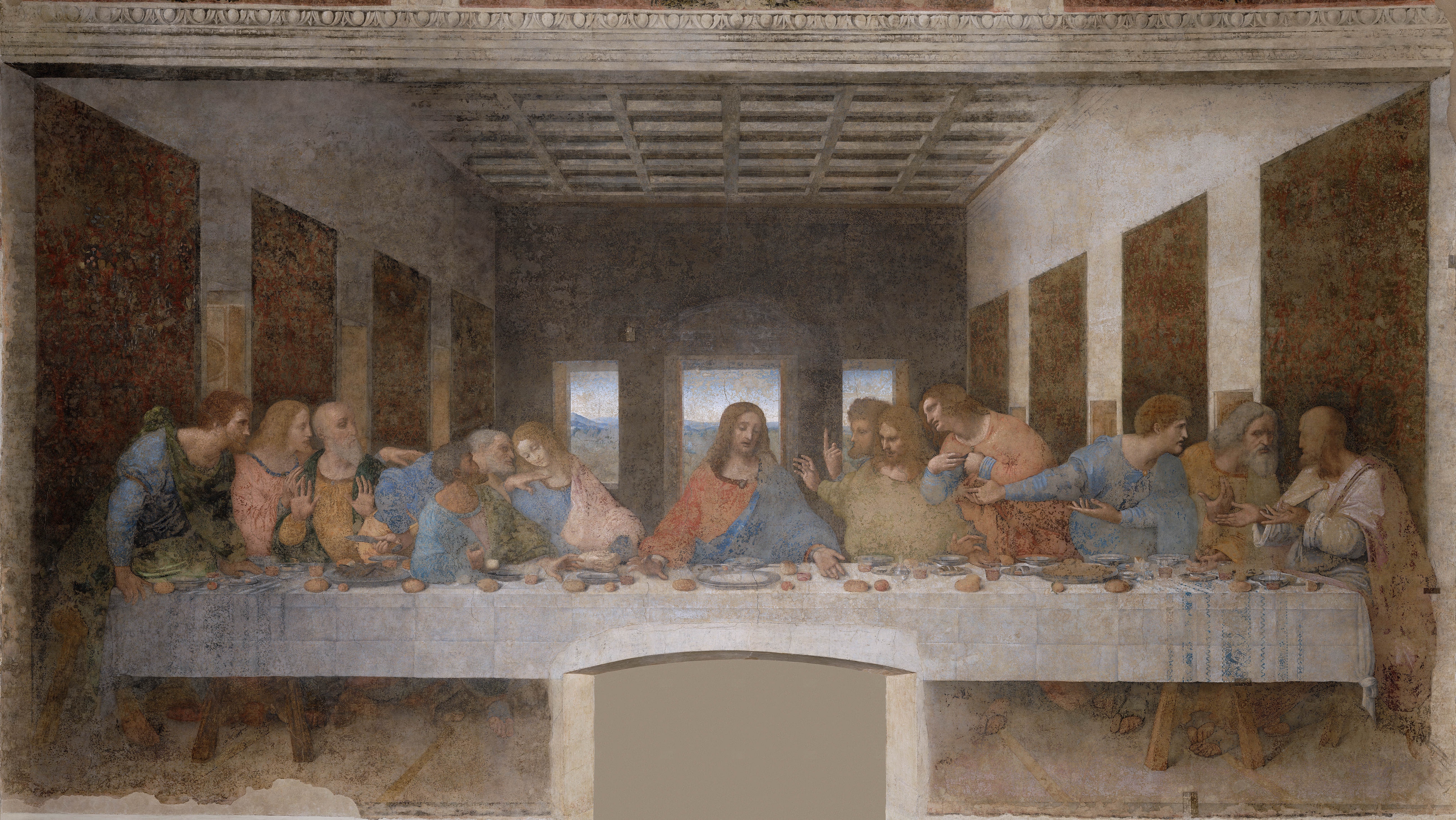

I want to start from Donna Haraway’s fascination with etymologies, and lead this into taking the title of her book, When Species Meet, seriously regarding the concept of “species.” As Haraway notes, “[c]ompanion comes from the Latin cum panis, ‘with bread’” (17). Companions are those who eat together, who share tables, who interweave and make each other through relationships and processes, entanglements with “partners [who] do not preexist their constitutive intra-action” (Haraway 32). She finds most delight in dogs, though other “animals” (I invoke Jacques Derrida’s skepticism) make an appearance. But back to the root: cum panis. Perhaps one imagines friends gathered at a table, sharing nourishment and conversation, furtive (or not) passing of scraps to a companion dog. Relations flow between these beings, all the connections and kin makings that Haraway delights in. But what of the bread itself? Made of wheat or other grains, food for many, I argue that we must consider this“kind” too. Plants make a limited appearance in Haraway’s book, coming alive mostly through the Canis-morphic “Jim’s Dog” (5-6). I argue that plants, too, deserve a seat at the table, and as more than objectified food. How to incorporate plants into the species part of Haraway’s “companion species,” given the word “species’” own root tied to “look[ing]” and “behold[ing],” may prove difficult for beings without eyes (potatoes forgiven for their transgression) (Haraway 17). Here, I will try to make comparisons for the sake of a generative discourse with Haraway’s concepts in order to explore whether plants can truly hold their own with animals as companion species.

Considering plants, or their mistaken cousins, fungi, as companion species, explicit or not, is certainly not without precedent. Michael Pollan’s book The Botany of Desire and Anna Tsing’s paper “Unruly Edges: Mushrooms as Companion Species” come to mind. As Tsing argues, “[c]ereals domesticated humans” (145; italics removed). According to her, the difficulty, rather than convenience, of cultivating wheat and barley over harvesting wild varieties allowed “social hierarchies” and “the state” to emerge and enforce patriarchal standards (Tsing 146). In essence, grains made us who and how we are at least as much as dogs have. Now I want to turn back to the sight-based root of “species.” Haraway writes an incisive criticism of Derrida and his cat, noting the difference between the cat looking back and the philosopher failing to think of “how to look back” and how to engender a responsive relationship with the cat (19-25; italics removed). In short, she criticizes Derrida for not recognizing, as she writes later, “the obligation to respond” (Haraway 80). In this case an “intersecting gaze” would have paved the way for true multi-species companionship, an “entanglement” that may not always be equal, but at least contains some core of trying to understand (Haraway 21, 20). How can this be for plants? Imagine if Derrida had walked into that bathroom on that morning and had seen his beloved houseplant. It is awfully hard to think of the plant looking back. Still, maybe the plant would have brown or wilting leaves, clearly a sign of distress. Derrida could have gone to the sink, poured some water in a cup, and tried to honor the plant’s distress signals. Would that count as response? Could Derrida feel shame in front of a plant? Even if he could, would that be a relationship with somebody, or something? Haraway implies that having a “face” means being “somebody” alongside being “something,” but plants don’t have faces or any other clearly recognizable sensory organs (76). How does one respond to something without a face?

Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4b/%C3%9Altima_Cena_-_Da_Vinci_5.jpg

Maybe touch will help sort things out. Haraway mentions “touch” as a part of “becoming with” (36). Certainly a human can touch a plant and a plant can touch a human (or any other being, for that matter). But are there implications in Haraway’s thoughts? She writes that “[t]hey touch; therefore they are” (Haraway 263). Of course, this is in the context of animals, but I think it holds. To further this idea, it might be good to look at a plant that has long enthralled people: Mimosa pudica. Also known as the sensitive plant, Mimosa responds to touch by curling its leaves in a remarkably short amount of time (Gagliano and Marder). As Monica Gagliano and Michael Marder write in an article for Botany One—critical plant studies is an emerging field with a small amount of scholarship—Mimosa at Kew Gardens “no longer curl up to the nudging fingers of countless human visitors” (para. 4). These Mimosa have learned, and they have done so through touch and response. Before getting too excited, however, it’s important to extrapolate Haraway’s warning that “resistance to human exceptionalism requires resistance to humanization” (52). While Mimosa do show, I believe, plants as “somebody,” they may better be seen as an anthropomorphic lure. Many have fallen into the trap—see, for example, Percy Bysshe Shelley’s quite animate and thoughtful “The Sensitive Plant.” We seem to love what is like us, and timely response fits. Focusing on Mimosa means entrenching ourselves further into the Humanist ideals that Haraway’s notion of companion species tries to resist. But even with other plants we just can’t help ourselves. Think, for example, of William Wordsworth’s “fluttering,” “dancing” daffodils, “tossing their heads” (6, 12). These flowers have faces, but are they not ours?

Source: http://www.nagwa.com/en/explainers/702159062142/

There are other issues too, the most problematic being Haraway’s ideas of play and suffering. Haraway describes play as something that “brings us into the open” and can lead to “joy” (237). Despite all of Wordsworth’s poetry, I cannot convince myself that we can play with plants, and that plants can play with us. The problem of suffering offers more traction. As Haraway notes, “[t]here is no way to eat and not to kill” (295). This implicates plants within the potential for suffering and “nonmimetic sharing” (Haraway 75). In response to the uncomfortable situation of suffering that we cannot literally share, Haraway suggests avoiding notions of sacrifice and instead learning to respond, ending up at the point of refusing “to separate the world’s beings into those who may be killed and those who may not”: “Thou Shalt not make killable” (79, 80). As Haraway uses the word “beings,” I’ll assume that plants fall under this maxim’s ethical purview. That also means acknowledging the suffering, however it is, of plants. Whether or not they feel pain (can we even make that equivalence?), I think we owe plants response, and in that response a responsibility for our cross-species interactions emerges. Cum panis takes on a cannibalistic undertone from this point of view, with all life forms consuming and using one another— “indigestion” indeed (Haraway 292)!

How do we make kin in a relationship this messy? To take Haraway’s approach, we should not only look—regard—but respond with the “risky obligation of curiosity,” learning to become worldly in the process (287, 3). With such complexity we may also learn even more acutely what it takes to “become with” (Haraway 3). So, are plants companion species? Haraway makes few if any sweeping statements in her book, substituting the goal of a unified theory for fluxes and specifics; “becoming” happens in the details. As well, she writes that “we learn to be worldly from grappling with, rather than generalizing from, the ordinary” (Haraway 3). Haraway’s focus on animals does not preclude plants from being a part of meeting species. Even if looking, touch, play, and suffering don’t fit, plants still shape us, and we shape them. So yes, plants are companion species with all the wonderful potentialities that recognition comes with. It’s companion species all the way down, cum panis to the root.

Works Cited

Gagliano, Monica, and Michael Marder. “What a Plant Learns. A Curious Case of Mimosa pudica.” Botany One, 2019, philosoplant.lareviewofbooks.org/?p=308. Accessed 19 Jan. 2022.

Haraway, Donna. When Species Meet, University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

Tsing, Anna. “Unruly Edges: Mushrooms as Companion Species.” Environmental Humanities, vol. 1, 2012, pp. 141-154. doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3610012.

Wordsworth, William. “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud.” Poetry Foundation, 2022, www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45521/i-wandered-lonely-as-a-cloud. Accessed 19 Jan. 2022.